In “Imperfect Storm” (part one), I spent time setting up how I am trying to use Edward Said’s notion of the “textual attitude” to think about superhero comic book continuity pedantry and its recapitulation of problematic, if not outright racist, tropes in that genre. In the interaction between X-Men’s Storm (aka Ororo Munroe) as a black African mutant superhero woman who has lost her powers and Forge, a Native American disabled mutant inventor, the first part of “Lifedeath” challenges the degree to which a subaltern identity can exist independently of the colonial history that has shaped those identities. Now I move on 12 issues later to “Lifedeath II.”

While “Lifedeath II” is a narrative departure from the rigmarole of X-Men continuity—taking a breath to try to examine the disjuncture between Ororo’s African origins and her superhero identity—it still reinforces a narrative of Africa as impoverished and superstitious. I am not trying to claim that there are no impoverished African countries, that there aren’t diverse sets of beliefs and customs, or that Africa doesn’t have its share of political and economic crises, but rather that Africa is not allowed to be anything more than those things in the Western imagination, nor are the colonial forces largely responsible for its current condition held accountable for the degree to which those stereotypes have truth. As I explained in Part One of this series, the schematic authority of the African “text” (i.e. the knowledge about Africa constructed by the West and its ideologies) asserts an essential abject condition for Africa and Africans. This is something that “Lifedeath II” continues to reinforce to varying degrees in service of giving Storm a depth not afforded most (if not all) black superheroes. As Jay Edidin and Miles Stokes suggest in Episode #45 of Jay & Miles X-Plain the X-Men, ,The Woman Who Could Fly,” which covers Uncanny X-Men #198 (1985) the issue “Lifedeath II” appears in, Storm is such a complex character it is really impossible to give a Storm “elevator pitch”—that is, a succinct and compelling encapsulation of her identity and her story is impossible.

While “Lifedeath II” is a narrative departure from the rigmarole of X-Men continuity—taking a breath to try to examine the disjuncture between Ororo’s African origins and her superhero identity—it still reinforces a narrative of Africa as impoverished and superstitious. I am not trying to claim that there are no impoverished African countries, that there aren’t diverse sets of beliefs and customs, or that Africa doesn’t have its share of political and economic crises, but rather that Africa is not allowed to be anything more than those things in the Western imagination, nor are the colonial forces largely responsible for its current condition held accountable for the degree to which those stereotypes have truth. As I explained in Part One of this series, the schematic authority of the African “text” (i.e. the knowledge about Africa constructed by the West and its ideologies) asserts an essential abject condition for Africa and Africans. This is something that “Lifedeath II” continues to reinforce to varying degrees in service of giving Storm a depth not afforded most (if not all) black superheroes. As Jay Edidin and Miles Stokes suggest in Episode #45 of Jay & Miles X-Plain the X-Men, ,The Woman Who Could Fly,” which covers Uncanny X-Men #198 (1985) the issue “Lifedeath II” appears in, Storm is such a complex character it is really impossible to give a Storm “elevator pitch”—that is, a succinct and compelling encapsulation of her identity and her story is impossible.

“Lifedeath II” opens with a callback to Uncanny X-Men #186. Between these issues a lot has happened to Storm as she tries to take her leave of absence from the X-Men to do her thing and find herself now that she’s lost her powers. In issue #196 she arrives in Africa only to be shot in the head and left for dead by the von Strucker Twins, the Nazi children of one of Captain America’s many Nazi foes, Baron Wolfgang Von Strucker. “Lifedeath I” opens with Storm lying despondently on a bed in Forge’s high-tech house and the caption reads “Once upon a time there was a woman that could fly…” creating a sharp juxtaposition between her curled up vulnerable form and the power of flight. Issue #198 opens with Ororo trudging through a sandstorm wrapped in a long robe, a bloody wound visible where her mohawk makes her scalp visible. The captions—now narrated by Ororo’s voice—read “Once upon a time there was a woman that could fly. Now, I walk…just like plain folks,” the last part echoing Forge’s sharp words from “Lifedeath I” when he tries to convince her with some tough love to go on living despite her loss of powers. However hard life may seem to her now that she has lost her powers, it is the life that most everyone else must lead.

This return to “a normal life” (or as normal as anyone in superhero comic books is allowed to have) and the difficulties that come along with it are reinforced by the punishing sandstorm and a set of disorienting scenes as Ororo tries to stay alive. The disorientation she experiences coheres in relation to the subtitle for “Lifedeath II,” which is a worrying “From the Heart of Darkness.” The subtitle makes me cringe, considering the lasting image of Africa depicted in Joseph Conrad’s The Heart of Darkness, and its influence on the Western perspective on other “untamed” parts of the world and the doubt of very possibility of “civilizing” the people that occupy the sites of Western imperial projects—consider Apocalypse Now’s reimagining of it for Vietnam. The allusion to Conrad, which may be an attempt by the writer here to connect his superhero comic to a more reputable literary tradition, suggests an essential chaos and meaninglessness that Africa encapsulates and shows the white man how thin the veneer of his civilization really is. The irony of course is that “Europe” has “Africa” beat by any measure when it comes to lasting and far-reaching legacy of chaos and violence, and being an example of the difficulty of lasting political stability.

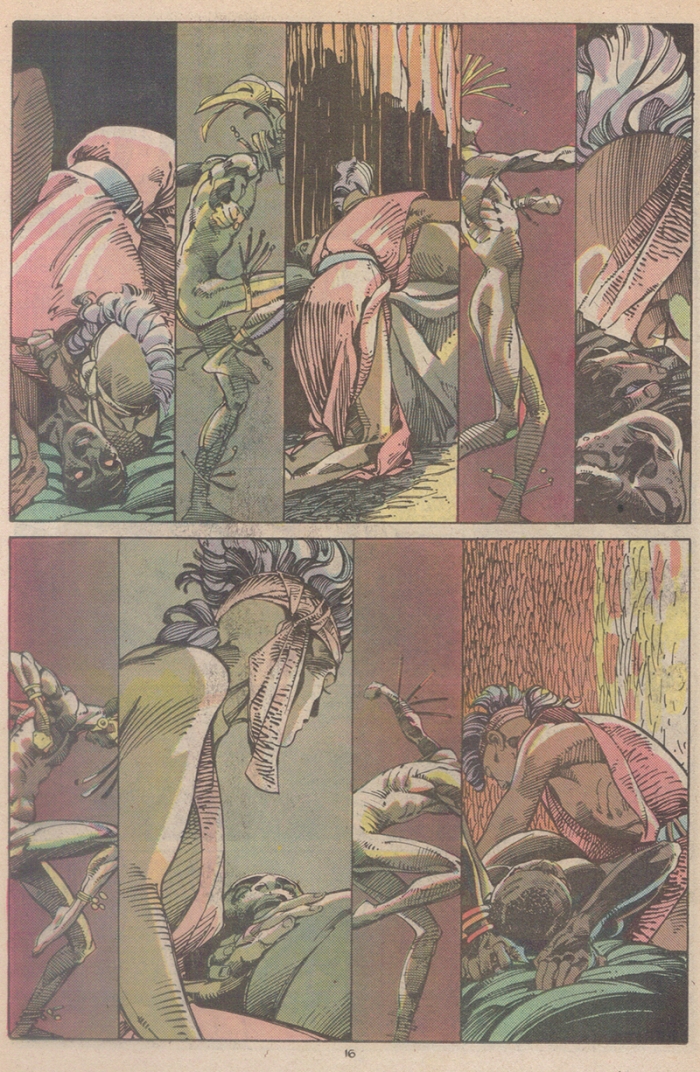

In the disorienting sequence of Ororo trapped in the sandstorm, words and images work together to evoke in the reader the feeling of Ororo’s return to her motherland. In a few short pages, Ororo goes from walking lost through the sandstorm, ostensibly unable to use her powers to keep herself safe or disperse the storm, to crying out to it in frustration to “Begone!” The skies clear up. She can suddenly fly again. But then collapses into Forge’s waiting arms as the mirage fades and the sandstorm returns. At first she is happy to see Forge and professes her love, but then rejects him (remembering his betrayal). She trips and falls over into the nest of a pit viper, which she wrestles in confusion, not sure if the snake has bit her. The image of Forge fades away. It is hard to deny that Claremont and Windsor-Smith’s mix of compressed panels and Ororo’s soliloquies work really well to depict not only Ororo’s mind state, but a sense of place through that confusion, but it rests on an image of Africa embedded in popular narratives.

Crawling into a cave for shelter and perhaps waiting to die of the snake’s venom, Ororo’s hallucinations continue. When the X-Men appear, Ororo begins to question her role in Professor Xavier’s project for mutant-kind. She blames them for her current situation, saying: “You took me from my home – because of you, I lost my soul, my oneness with the world! I lost my powers of a goddess! I have become nothing!” But her anger at the X-Men is simultaneously an anger with herself, when comforted by an illusory Jean Grey, Ororo bemoans being unable to save her from her fate (remember at this point Jean Grey/Phoenix has been dead since Uncanny X-Men #138 (1979) and had not returned yet). Ororo’s sense that she may not belong to the world of the X-Men after all, and that as a part of it she is also a failure, strikes me as an echo of the colonial subject that is forced to adopt the occupier’s culture, but is also forever reminded that she will never be a member of the culture, is not “good enough” to remain, forever separate to some degree from both the original culture, and the colonizer’s idealized vision of their own value.

Ororo’s confrontation with the Charles Xavier vision reinforces her struggle with a colonial mindset. She rejects his interpretation of the events of Giant Size X-Men #1 when she joined the team. He claims he took her from her “nest and force [her] to fly.” According to this vision of Professor X, convincing her to leave Kenya and her relationship to other African people was for her own good. If she had not joined the X-Men she would have “remained an infant and probably perished with this land.” Prof X’s patronizing attitude could be attributed to Ororo’s mind state, but his statement is in keeping with a Charles Xavier who is frequently depicted as arrogant, self-serving and sometimes cruel, despite his professed progressive aims. What matters here, however, is that Ororo is struggling with an attitude she knows is embedded in the power relations between her land of origin and the Western world. She was convinced to leave Africa to help “the world,” as if Africa were not in the world, and thus nothing she could do there mattered.

Ororo awakens to find that she is not poisoned, but still entangled in a conflict with the viper, however, instead of fighting she gives it the mutual “respect” it deserves and it slithers away. The snake is an apt metaphor for Ororo’s struggles and the cloying coils of colonialism, but the “fundamental respect” thing seems a little too much like the “Earth Mother” trope. Ororo has no special powers regarding animals. An aggravated viper is not going to just slither away because you stop fighting and “respect” it. I guess if I am feeling generous I can imagine that the snake is also a hallucination, but otherwise the conclusion smacks a bit too much of a recapitulation of black and brown folks being closer to nature and animals, like born natural Tarzans. Regardless, she continues her march through the desert, now apparently clear-headed, but no less lost.

The rest of the issue focuses on Ororo helping a very pregnant young woman named Shani (the only survivor of a bus that crashed in the storm) who is trying to get back to her unnamed village to give birth so that her child might have a connection to the place where its mother is from. Shani’s pilgrimage very clearly parallels Ororo’s. The young pregnant woman says to Ororo quite explicitly, “Nothing is more important than that sense of place, of belonging.” Ororo and Shani, two black women, together in Africa discussing the meaning of place and the power of familial and cultural connections is radical for American superhero comics. Shani is the kind of character that often goes unnamed and unconsidered in Western literature, but she manifests in the comic as a version of the reality that Ororo is supposed to be a metaphor for—returning home, reconnecting, fearing reactions from old friends and family, finding both the place and yourself changed, and yet only feeling that way because of the importance of the connection.

In her seminal work of postcolonial theory, “Can the Subaltern Speak?” Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak answers her question with a fairly clear, “No. They cannot.” In fact, in a later interview Spivak would go further to say that in her view it is this inability to ever be heard that defines the subaltern, and that it is not a term to mean any oppressed person—though plenty of thinkers have been using is more broadly for decades much to Spivak’s chagrin. I have an article currently under review with an academic journal exploring this concept in terms of Latina superheroes and comics readers, but here I want to consider Shani as a possible example of that voiceless subaltern subject. It is not that she does not get to tell her story—village girl drawn to a varyingly wonderful and cruel city life who, finding herself pregnant with a child whose father wanted no part of it, returns to her people anxious that her parents and neighbors will judge her—but rather that that whole story is not really hers. As Spivak says, “the only way that [so-called subaltern speech] is produced is by inserting the subaltern into the circuit of hegemony.” Shani and her struggle exist in “Lifedeath II” as an element of Ororo’s story of trying to reconnect with her own roots. Shani has a voice here because of point of contact with a figure (however marginal) of the dominant social and political forces whose narrative is really doing the speaking for the typically overlooked subaltern subject.

For what it’s worth, Shani’s story is well done. It may verge on cliché, but Claremont does a good job of expressing the varied mix of attitudes and feelings about her choices that you could expect a person to have. She is not a caricature, but she does serve to provide a model for courage that Ororo admires and wants to emulate—one that is entwined with the uncertainty of being human, something that Ororo abandoned in being a goddess and a superhero to her own detriment. As Ororo thinks to herself as she walks Shani back to her village through the night, admiring Shani’s nerve, “What a sham I was! Storm – the paragon of virtue and courage – the goddess who soared above the common herd. Untouched and untouchable!” It is easy to seem brave when you can fly and shoot lightning out of your hands.

Shani is a fine character. She has a name, a story, a motivation and is drawn with generosity and respect. And while it may be easy to dismiss her, as she never re-appears after this issue, I think the less a character like Shani is in contact with serialized superhero stories the better, or she’ll end up remade in Spiral’s Body Shoppe or to have been an Inhuman all along, or something similarly undignified. I mean, compared to the latest Avengers movie’s use of an African setting as a nameless set-piece for a fight between Iron Man and the Hulk, Shani and her people have a sense of depth and reality to them. This is probably the best she can be represented in this genre. I am not sure what that means, but it is something to think about. She can have no voice outside of its use for that genre’s narratives. Even when Ororo must help her through a difficult childbirth, the birth itself works to echo Ororo’s coming re-birth, coming to a new understanding of herself that goes beyond her (now lost) powers. Just as Shani’s baby needs CPR in order to draw its first breath on its own, Ororo needs her own help to get past the trauma of being born (or born again) in order to go on living (and in her case, to go on superheroing).

The childbirth occurs in Shani’s village, and the focus of “Lifedeath II” switches to Ororo’s talks with the village elder, Mjnari. There is richness to how Claremont layers plots and themes in the X-Men of this era. We understand how Ororo suffers the birth pangs of a changing identity through her interactions with Shani, but the foundational connection of life and death is evoked through Mjnari and the ecological concerns of the village he advises.

The village and the villagers are not depicted in any way that is particularly identifiable as Kenyan. Then again, Ororo may not be back in Kenya. All we know as readers is that she is in “East Africa,” which is huge and diverse area to narrow down to just two words no matter how it is measured. Ultimately, I can’t help but wonder if Windsor-Smith just tries to evoke a generic East African look and feel, counting on Western reader ignorance and/or pre-determined ideas to develop an “authentic” feel. I think he (perhaps, unfortunately) succeeds. Even in episode #45 of Jay & Miles X-Plain the X-Men, Miles Stokes says “I don’t know if this is actually accurate for what anything is actually like in East Africa, either in terms of geography or in terms of the culture…but I will say it is beautiful both thematically and visually.” He’s not wrong. It is beautiful, and that beauty goes a long way in establishing that sense of authenticity even if it has been completely fabricated or misrepresented.

Barry Windsor-Smith is inking and coloring himself in this issue, giving an elongated and distorted sense to the figures that evokes movement and life, and lots of detailed lines that give each panel the sense that they could be transformed into stain glass scenes in a church window. This is most obvious when he intersplices panels depicting Ororo helping Shani give birth to her baby with images of the villagers performing a ceremonial dance to supplicate the spirits for a successful birth. The layout of the panels provides a sense of rhythm that evokes the musicality and desperation of the conjoined scenes (in a way that only sequential art can accomplish). Or check out this page where he succeeds at simultaneously evoking the intimate and immediate and the vast and cosmic.

Storm is a transcultural figure, and moving back and forth between cultures means she is vulnerable towards assumptions influenced by her relative privilege.

The ceremonial dance itself is a productive site for considering the positive representation of an African cultural practice. In the same episode of the X-Plain the X-Men podcast mentioned above, Jay Edidin clearly points out what hopefully any engaged reader would notice: that even Storm can have paternalistic attitudes towards the people with whom she ostensibly shares some cultural origins. When she sees the dancing she says to Mjnari that “A hospital would be of more use” than the dancing, assuming to know better than some “primitive” practice. But Mjnari explains that it is not that they believe such a dance to be superior to medicine, but that they have no vehicle to bring her to hospital and even if they did, they would not get to a hospital in time. Shani and her baby would likely not survive the trip. Imagine Ororo chastising someone in the West for going to church to pray for someone’s health because she assumed that was all that person knows to do. While the conversation quickly changes to the matter at hand, that moment produces the possibility to understand Ororo not as “an African woman,” but as a transcultural Westerner (and by trans- I mean moving back and forth), someone who despite her recent loss of mutant power, still retains an overwhelming amount of privilege not only in material wealth, but in assumptions about the way the world works.

Such assumptions may undergird this entire narrative, since this depiction of “Africa” coheres because of a reader’s willingness to accept this as representing some essential idea of the place (as if such a thing could ever exist outside of the realm of ideas), but at the same time the story resists the cartoon versions of “Africa” just as readily accepted by Western comic book audiences. All one need do is read some issues of Shanna the She-Devil (before they moved her to the Savage Land to avoid those complications) to understand that version is alive and well in the Western imagination. Instead, Mjnari seeks to impart a wisdom to Ororo that resists absolutes, even if ultimately the comic must recapitulate some stereotypes to make them legible for its audience. Mjnari’s wisdom emerges from understanding that there is no returning to a pre-contact pre-colonial state, but that regardless of how much damage has been done by greedy and/or thoughtless attempts to exploit these lands, or how romanticized the idea of unadulterated culture may be, that moving forward means finding a way to navigate a cultural hybridity that now exists.

When Ororo and Shani came upon the village at dawn, they discovered the remains of abandoned machinery that Windsor-Smith draws with a nod to Kirby, though there is nothing cosmic or particularly sinister about them. The land around the village, once green and plentiful in Shani’s memory is returning to the desert. Mjnari explains that when

“the outlanders came with their machines and their technology, promising to make the desert bloom, and the proved as good as their word – -our land turned green and verdant…but each year more fertilizer was required to raise the same amount of food… the simoon winds blew away the top soil…There was war. It became harder and harder to acquire fuel for the machines. And when they broke down…we could not afford parts to fix them…”

Mjnari is presenting a familiar narrative of the devouring capitalist drive of colonialism, forcing the colonized subject out of a hard, but sustainable, life and into an impoverished one beholden to western powers. At issue’s end, immediately after Shani’s baby is born Mjnari walks out of the village out into the desert, followed by a confused Ororo. It is clear to her that he has come out here to die, and after trying to explain to her about the village’s predicament he does just that—he wills himself to die. I think his death is meant to a noble and selfless act, as the village can only sustain a certain number of people. A new life arrives and old life must leave (though that doesn’t answer how Shani’s presence might also throw the balance out of whack), but Mjnari’s lesson seems couched in an oversimplified notion of the “balance of nature” or his people living in “balance” with their environment, what he describes as necessary for his people to survive and prosper is some middle ground to be found between the forces that sought to exploit this land to maximize its output and the traditions that are now insufficient to maintain even a hardscrabble life in the transformed physical and economic landscape.

Of course, the Mjnari’s dialogue still manages to downplay the responsibility of the colonial forces that re-shaped the continent in their scramble to gain control before their economic and political competitors did, but that is not surprising. The outlanders are “arrogant,” but never evil. The dehumanization of Africans is never mentioned. In order for Mjnari to remain a sympathetic character to the imagined audience of 1980s X-Men comics, he could not appear to be angry or militant to any degree.

Of course, the Mjnari’s dialogue still manages to downplay the responsibility of the colonial forces that re-shaped the continent in their scramble to gain control before their economic and political competitors did, but that is not surprising. The outlanders are “arrogant,” but never evil. The dehumanization of Africans is never mentioned. In order for Mjnari to remain a sympathetic character to the imagined audience of 1980s X-Men comics, he could not appear to be angry or militant to any degree.

Ororo hears Mjnari’s voice on the plain after his passing: “A bridge is needed between these two halves of the world – a synthesis, a blend – a person who is both one and the other, whose mind comprehends and whose hands command the machines…” Ororo realizes that she is the person Mjnari is talking about. The moment of revelation leads Ororo to claim the whole world as her home, an idea that echoes back to Professor Xavier’s words to her back in Giant Size X-Men #1.

At my most cynical I read this conclusion as a Wizard of Oz moment where Ororo had the power to “go home” all along. Just as Shani’s story and even her baby are just narratives tools to develop Ororo’s character, so is the very idea of this place and its postcolonial globalized struggle. Ororo goes on this journey to find herself after her loss of powers, but discovers that the hybrid-self made of different cultural influences cannot be tied to any one place. In Part One of this series I mentioned how X-Men comics inhabit hybrid zones—a mix of cultural notions and threads of identity that can be (and have been) put to work in myriad ways as metaphor for race and sexuality and adolescence and the dynamics of oppression and resistance. X-Men as a serialized superhero narrative has been one of the most elastic and unstable ones—as comics creator Daryl Ayo suggests, X-Men is nearly a genre unto itself—providing a site for exploring myriad mutually constitutive identities and imbricating the individual notion of the self with various marginalized group identities by positioning facets of this hybridity as central to any given narrative conflict. In other words, Storm is black and African and a woman and a mutant and an X-Man and maybe queer, and while any one of these identities will be put to the fore at any given time, in truth they all help to define each other inextricably. It is just that in any given context one appears ascendant. As such, declarations of world citizenship like those expressed here conveniently ignore the specificity of the power dynamics between nations and peoples of the Earth. It remains mysterious to, however, how we can feel ourselves to have a coherent identity without erasing what Said called, “disorientations of direct encounters with the human,” which disallows for simple categories and a sense of wholeness.

At my most cynical I read this conclusion as a Wizard of Oz moment where Ororo had the power to “go home” all along. Just as Shani’s story and even her baby are just narratives tools to develop Ororo’s character, so is the very idea of this place and its postcolonial globalized struggle. Ororo goes on this journey to find herself after her loss of powers, but discovers that the hybrid-self made of different cultural influences cannot be tied to any one place. In Part One of this series I mentioned how X-Men comics inhabit hybrid zones—a mix of cultural notions and threads of identity that can be (and have been) put to work in myriad ways as metaphor for race and sexuality and adolescence and the dynamics of oppression and resistance. X-Men as a serialized superhero narrative has been one of the most elastic and unstable ones—as comics creator Daryl Ayo suggests, X-Men is nearly a genre unto itself—providing a site for exploring myriad mutually constitutive identities and imbricating the individual notion of the self with various marginalized group identities by positioning facets of this hybridity as central to any given narrative conflict. In other words, Storm is black and African and a woman and a mutant and an X-Man and maybe queer, and while any one of these identities will be put to the fore at any given time, in truth they all help to define each other inextricably. It is just that in any given context one appears ascendant. As such, declarations of world citizenship like those expressed here conveniently ignore the specificity of the power dynamics between nations and peoples of the Earth. It remains mysterious to, however, how we can feel ourselves to have a coherent identity without erasing what Said called, “disorientations of direct encounters with the human,” which disallows for simple categories and a sense of wholeness.

Nevertheless, feeling like a whole person once again, and convinced that having her feet in different worlds gives her a responsibility to those worlds, Storm is reborn, and that is great because it grants a black superhero character (man or woman) a depth that I would argue is unparalleled in any mainstream superhero comic. And yet, after this Ororo will return to the X-Men and Shani and her village and East Africa will be basically forgotten for 30 years. In the final part of this examination of Storm I will look at her return to East Africa in 2015’s Storm #3.

Despite the pleasure of reading both Uncanny X-Men #186 and #198—both parts of the “Lifedeath” dyptch—and my feeling that they stand with some of the most-lauded comics of the 1980s that were notable for their departure from canonical approaches, ultimately, however impressive they might be for their art and storytelling they are still stark reminders of voices missing from mainstream comics (and to a large degree indie comics as well) and the limits of all (even well-intentioned) representations. “Lifedeath” is another one of those make-do moments, where even in admiring the craft of its formal elements, you can’t help but wonder if our orientation towards a text’s content always serve dubious hierarchies.

Pingback: Imperfect Storm (Part One): Exploring “Lifedeath” | The Middle Spaces

Pingback: Imperfect Storm (Part Three): “Return of the Goddess” | The Middle Spaces

Pingback: Additions, Corrections, Retractions | The Middle Spaces

Pingback: Striking Back: Black Lightning and Reading Race (part two) | The Middle Spaces

Pingback: Seeing Sounds / Hearing Pictures – A Round Table on Sound & Comics (part three) | The Middle Spaces

Pingback: Epic Disasters: Revisiting Marvel & DC’s 1980s Famine Relief Comics | The Middle Spaces